A woman gradually learns to not just look,

but to squint and to peer, and then, more and more,

to suffer no fools.

— Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Women Who Run With The Wolves

☁️

My sister said, “People reinvent themselves all the time.”

I got my nails painted a shade of brown so dark it looked black. I told my ex I chose the color as a symbol of death and rebirth. He said, “You sound like one of the goth kids from South Park.” And, despite any remaining notes of depression, I laughed. That night I went doom scrolling. I dove deeper and deeper into recesses of the internet as an anesthetic for my incurable longing. At some point I came across a carousel of quotes on Instagram titled: “How To Not Fear The Dark”. The one that stuck with me said: “Let us talk more of how dark the beginning of a day is.” After that, I interpreted the first real snow as a relief: finally, there were no sunny reminders. I looked at a field and saw my own mood reflected back, heavy and anxious to start the whole world over. It gave me hope: the sight of untouched snow can be clarifying, like a metaphor for resolve. I told my ex some variation of this sentiment, and he said, “You just like the winter because then everyone’s as sad as you.” And, once again, despite myself, I laughed. Eventually, I succumbed to a meditation’s suggestion: I started doing body scans. I realized that depression wasn’t my only problem—of course there was anxiety. (Why wouldn’t there be?) Every night, in bed, my leg clenched and unclenched as if I’d survived Vietnam; I desperately clung to the small moments of solace I found in the white glow of my kindle, reading novels about cannibals. The themes of romance—of love and family—lit up like a christmas tree against a backdrop of depravity. One of the books I read was about a dystopian world where all the animals have been rendered unsafe for consumption by some novel virus. As a solution, the government starts breeding humans for meat. Giving the reader a tour of the facility, describing a horror show of severed vocal cords and packaged brains, the narrator asks: “How many hearts need to be stored in boxes for the pain to be transformed into something else?”

That’s the annoying thing about healing, I thought, all you can do is wait.

I found myself in the land of Bella Swan for the holidays: the pacific northwest. Staring out a car window, looking at a recession of towering, wet evergreens, I could almost hear Lykke Li’s “Possibility”. (In other words: I was 2,552 miles away from home and I still felt depressed.) I wrote out my cognitive distortions like a wishlist for my therapist. My personal favorite occupied the very last slot: Every relationship I’ve ever been in feels like a lie. I texted my old situationship a paragraph on Christmas Day. (What better way to celebrate the birth of Jesus than by announcing one’s unrequited love?) I wrote in my journal: I have no interest in revenge or some radical reinvention of self that projects some badass form of autonomy and independence. I just want accountability, recognition and understanding. Why do these things feel so impossible? (He didn’t text back.) Scrolling through TikTok, some girl came up on my ForYou page. She said that if you want men to be attracted to you, then you can’t be the “needy paragraphs” girl. She said a woman needs to be a cold, withholding bitch because: “He’s not reading your paragraphs, girl.” And, personally, I felt attacked. So I came at her sideways in the comments, “All I’m getting from this is that men don’t respect women, like at all.” After that, I texted my ex, “Why do I always fixate on the one person who can’t see me?” And he texted back, “I feel like you think everyone is some diamond in the rough, and they’re just not. Sometimes people are exactly who they show you they are, and if a person acts like a piece of shit then they’re a piece of shit.” I remembered what my therapist said, “It hurts when you have a big heart and you don’t see that being reflected back.” I wrote in my journal: A lack of closure and accepting that lack is its own kind of existential torture. I cried to my mother, “Why is nothing ever enough for me?” Channeling the book on her nightstand (Stop Walking On Eggshells: Taking Back Your Life When Someone You Care About Has Borderline Personality) she said, “From everything I’ve read, you can’t help what you’re feeling.”

I brought in the New Year by watching all three Tobey Maguire Spider-Man movies in chronological order.

When the clock struck midnight, I was all alone. The credits rolled and Dashboard Confessional sang about hope dangling on a string like slow spinning redemption. I made the same promise that every other person was making from coast to coast: This year will be different. But then I back tracked. A few days later, I slipped into old habits by bickering and ruining what could have been a nice lunch with my sister. She told me some variation of: Think about how much your crying affects mom. And I snapped, “I’m the one who experiences my mental illness firsthand.” (That’s the downside to being around family: you revert back to dated narratives and old roles. Cognitive distortions run rampant and you grow paranoid waiting for the inevitable criticism. You tell yourself: I am the runt of the litter, until it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.) That night, we sat down to watch Everything Everywhere All At Once as a family. Across an infinite number of universes, I watched as a mother and daughter struggled to understand each other. In one universe, the mother is a scientist who uses the daughter as a guinea pig for a “verse jumping” experiment; she pushes her to the precipice of human experience. As a result, the daughter’s mind is permanently fractured; she comes unstuck in the multiverse and is torn apart by every possible reality. She loses all sense of morality and any belief in objective truth, making her the ultimate agent of chaos. No one in the multiverse can decipher her motives, not even herself. She tells her mother that she’s desperate to share her perspective—for someone to feel what she feels. She says, “I’ve been trapped like this for so long, experiencing everything. I was hoping you’d see something I didn’t, that you’d convince me there was another way.” (I felt something more than numbness for the first time in months.) Toward the end of my vacation, overwhelmed by the reality that me and my parents would be leaving, my five year old niece had a monumental tantrum. From underneath the dining room table, she bellowed as I rubbed her back. (I could understand her better than anyone: a chronic fear of abandonment is at the core of my personality. Even the anticipated pain of being left is all encompassing and soul crushing. If it was too big for me, then it was certainly too big for such a tiny body.) At that moment, she was the only person in the world who made any sense to me.

I wrote in my journal: I know it sounds so childish, but why can’t something just go my way?

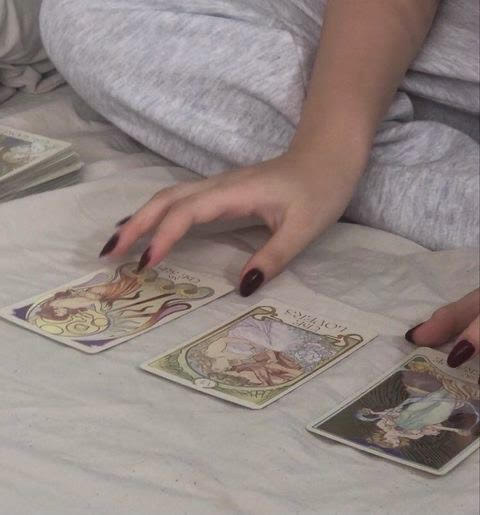

When I got home from Seattle, in a collective attempt to minimize my rage, my friends and I sat around psychoanalyzing my situationship. (He was emotionally constipated and needed to cry. He was traumatized by his relationship with his father. He didn’t mean to be such a liar, he just grew up in a home where the truth made no difference.) I read a line in a book that reminded me of him: “The problem is most people don’t know their psychological realities.” I asked a tarot girl on TikTok if he and I would ever make amends. She said, “He’s content with where he’s at.” And I wrote back to her in the comments, “I love that for him.” Later, during another round of group psychoanalysis, my friend said, “Men drain the women they date of everything and feed on their life forces.” And all I could think about was how one of my other friend’s exes popped the flower balloon she won at the fair, on purpose. Eventually my friend revealed something my situationship said about me. He said, “You have no idea what she put me through.” And I was taken aback. On the defense, I cited my emaciated body and the bags beneath my eyes and the resounding months of depression; the psychological fragmentation that results from being on the other end of the cognitive dissonance of a man who’s hurting you as he says he’s not hurting you; how, sometimes, in the months that succeeded him, the emotional pain was so intense all I could do was physically run from it. (People will break you and then blame you for being broken, I swear. It had always been about him, constant and grating, like clenching your jaw when you’re trying to sleep. My dopamine receptors were burnt out from rearranging my thoughts and days around him like furniture. My friend was right: some men just want to be loved and it will suck you dry.) On TikTok, a girl said that people with abusive mentalities conflate vulnerability with harm; they believe that anytime they feel vulnerable, they are the victim. “Cat,” my friend said, “your existence is a wound to him.”

That did it: I needed to evict him from my mind.

I wrote a little inspiration on a piece of paper like a Dove chocolate wrapper: Fall in love a little bit everyday. And then I took it literally. This little exercise in daily gratitude resulted in an arbitrary crush on a guy I’d casually walked past almost everyday for a year. Trying to be more mindful of the little things, I’d started to notice that he moved with a subtle bravado that I’ve always found attractive; and, instead of remaining limited to the realms of admiration, I had to see it through to the bitter end. Of course I messaged him on Facebook. The conversation, however, ebbed and flowed with wide gaps in between—and not because of me: our talking was constantly at his mercy. I sat around, pulling at my eyebrows, waiting, living for the thrill of never knowing when he was going to disappear entirely. (I had a phone full of guys constantly vying for my attention—naturally I wanted the one whose only comment on my appearance had been one of neutrality: “You have little knees.”) Because who was I without the drama and constant influx of cortisol? A line in a book appropriately titled Acts of Desperation stuck out to me: “Going through life hungover is an ordeal, but being without one is no picnic either.” I suffered in silence until it finally happened: The Crush heart-reacted my Facebook story. I shaved and moisturized my entire body: I’d manifested this, goddammit. The next night, he resurfaced via text and we hung out. We smoked a blunt and he made a smart remark about my ghost socks and Pusheen calendar. Ultimately making me wonder: Am I high or is he negging me? This set the tone: it was one long night of strained interactions. He asked me to list my top five favorite shows, and I immediately felt challenged. (He was establishing himself as a guy who believed a person’s shallowest interests created an accurate impression.) My mind went blank and I felt like he could see me malfunctioning as I became overloaded with the task of computing what “boys” liked. I blurted out, “Do you watch It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia?” And he gave me a look, like he knew exactly what box I was locking him into. Later I joked about pushing him backward into a pipe that would have served a lethal blow to the back of the head—it was probably really weird for him. And then, when we hooked up, I realized my situationship had made me sexually strange. (I was afraid to touch him below the neck, and when he asked for a condom, I told him I had Plan B.)

He receded into the night and ghosted me entirely.

After that, I consulted my friend. I said, “So there’s this guy that I talk to a little bit everyday. And he talks to me a little bit everyday. And I don’t understand what he’s, like, getting from it.” My friend made a little rainbow with her hands; she said, “Hear me out: friendship?” After constantly feeling used and objectified, the concept of “taking things slow” came as a surprise. Friendship? I was shocked by the revelation. Later that night, a TikTok captioned with “when I find a new guy to be absolutely insanely obsessed with so I can forget about the last guy I was psychotically irrationally obsessed with” came up on my ForYou page. The signs were there: I’d merely slapped a bandaid on top of another bandaid, making it more difficult to get to the wound. I wrote in my journal: I really liked someone and I really wanted to be with him, but it didn’t work out. And sooner or later, I have to try to get over that—lest I want to appear as a giant walking red flag to every other guy I happen to be interested in. I recognized all of this, and yet: obsessing over what was wrong with me through the eyes of some arbitrarily chosen male was saving me from being existentially bored. Therefore I took an inventory of my missteps: I live in an unfinished basement. I have a cache of psych meds on my nightstand. I’m a thirty year old woman with stuffed animals. I told my friend, “I burp-growled in his face, like—I emitted that noise from The Grudge.” And she assured me, “You’re a legend.” (I remained unconvinced of my greatness.) Another friend told me about a term for when a person seeks out information that they know will hurt them—a term which now escapes me—and I immediately engaged in the behavior by googling: “signs he regrets sleeping with you.” (The Crush met four out of the ten criteria, and the other six simply weren’t applicable.) Out of nowhere, I was reminded of this Sarah Dessen novel that I read in highschool called Someone Like You. I remembered it as a cautionary tale about a teenage girl who loses her virginity to her boyfriend and never hears from him again. I checked it out from the library: it felt appropriate, considering the circumstances. About twenty pages in, however, I realized I’d misremembered it. It was not a story of abandonment, but a coming of age tale about a girl who discovers her worth. Halley, the main character, is in search of an identity, but—throughout the course of the novel, believing that her own life is boring and not worth noting—she spends her time trying to escape the difficulty of self-actualization by losing herself in her inadequate, however exciting, boyfriend named Macon. Describing her first kiss with him, Halley says: “I wasn’t even myself anymore. I could have been any girl, someone bold and reckless. There was something about Macon that made me act different, giving that black outline some inside color, at last.” And yet, she never sleeps with him. She saves herself in the end by “working a little magic of her own.” As a 30 year old woman, I had yet to internalize the story’s message, and I wasn’t ready to deal with it.

I matched with my situationship on Valentine’s Day instead.

I sent him a message, “Deja vu?” And then I promptly threw my phone across the room. (Surprise, surprise: he never replied.) Staying true to the theme of revisiting shitty Y2K literature, I checked out He’s Just Not That Into You from the library. (A dating advice book focusing on the wisdom of a guy named Greg—a random mediocre white man with frosted tips and a soul patch—who, naturally, interrupted a woman and got a whole book deal out of it.) The book was a disorienting combination of fonts, filled with a collection of glittering dating tidbits, such as: “Men are never too busy to get what they want.” Ignoring the bulk of the book’s advice, still obsessing over what I got wrong with The Crush, I listened to a podcast centering on another Y2K dating book called The Game. The hosts recounted passages outlining advice for men on how to pick up women; advice that suggested a man keep a small black light on hand, just in case he needed to neg a woman about her dandruff and thus convince her to sleep with him. This information quickly debunked the simplicity of He’s Just Not That Into You’s concept. (The Crush just wasn’t that into me.) And I thought: Okay, but men do play games. On FaceBook, I messaged a guy I’d been infatuated with as a teen at church camp. I asked him whether my BPD diagnosis made sense, considering he’d known me as a kid and I’d had an abnormally intense crush on him. He said, “I don’t know, that stuff’s hard to see when you’re so young.” And then he added, “I also had an abnormally intense crush on you.” This information only made my predicament more confusing: as a kid, I’d been convinced that, not only did he not like me back, but I’d annoyed the absolute shit out of him. He said, “I should have acted more obviously infatuated.” (I deemed him completely useless.) Finally, I decided to confront The Crush head on. “What’s the deal?” I texted him. And he gave me a hodgepodge of classic, however respectable, excuses. (He was anxious. He was just coming out of a relationship. He was trying to regain some independence. He liked me, but—) Unfortunately this tangible piece of closure did little to quell my preoccupation. I wrote in my journal: I just don’t want to think about it or care anymore. I told my therapist about how I couldn’t stop dwelling on my rejections; that on top of everything else, I missed my ex of four years and wondered whether these were all signs pointing me back to him. “Well,” she said, “do you want stability, or the thrill of the chase?” And I said, “Honestly, neither.”

That night, I had a dream that I lost my shoes in the rain.

They were brand new: a trendy pair of black chunky patent leather heels. I was walking in the rain to a party with friends and the shoes were preventing me from keeping up with them. Eventually I got so annoyed I took them off and replaced them with a pair of men’s Crocs that I found floating in the gutter. But, as it turned out, those wouldn’t do either: they were too big. So I ditched the Crocs, too. I walked the rest of the way barefoot. When I got to the party, I kept laughing at myself, unable to remember how I lost my shoes. “I’m barefoot at a party. Who does that?” I kept asking. (Nobody laughed with me.) When I awoke, I immediately Googled: What does a dream about lost shoes mean? And I read about how lost shoes represent a struggle to find one’s way in waking life, a total loss of identity. One article talked about the loss of security, a lack of fulfillment in relationships and a disruption in one’s self-image without the validation of another person. It said: “Maybe a situation has come along and made you realize that your opinion of yourself is flawed.” I watched a YouTube video about boundaries and people with BPD. The psychologist explained that, when a relationship with a significant other has been fractured, a person with BPD can be left feeling desperate to re-find an external object to provide stability. I tried not to think about my ex; my nightly existential crises that left me sick with anxiety, wondering what was going to happen to me without him. As a distraction, I went out with friends. They got fucked up and hooked me up with a basketball player—they understood that, living a life free of alcohol, men were the only vice I had left. Naturally, The Basketball Player stuck out above everyone else; he had gleaming teeth that said he wasn’t from here, and a look of fatigue that said he was already tired of it. As we talked, he dissected me into parts. He said, “You’ve got the face and the shoulders and the stomach.” He said, “My night was boring until now,” and I experienced the adrenaline rush of a magician’s assistant about to be sawed in half. Of course I hung out with him a few days later, and of course it didn’t go according to plan.

We shared a blunt and I experienced an ego shattering high.

Earlier, when I first arrived, he explained to me that his dog was a rescue with an anxiety disorder—she got so nervous, sometimes she’d eat the wall. I tried referencing this to make light of my panic. I said, “Now you have two anxious animals!” But The Basketball Player didn’t get the joke. Eventually my anxiety got so bad that I started trauma-dumping all over him; I said something, like: Some part of me used to think that I was just making it all up, that I was just lazy and incapable of getting my shit together. But then I get stoned and I feel how real everything is all at once; and it’s hard not to feel sorry for myself—like it’s hard not to feel sad about everything mental illness has taken from me. It’s weird to realize that I’m stunted, and it’s not necessarily my fault; but so many people are going to look at me and see a smart, able bodied person, and just reinforce all of my worst fears about myself. When I’m high, I realize I’m always in so much emotional pain that I’m constantly working to intellectualize it, just to function. And, like: this is it for me. I’m going to be working to manage this for the rest of my life. If I didn’t have to spend so much time focusing on that, would I be capable of so much more? The Basketball Player looked at me and said, “I hear what you’re saying, but, at the same time, some people just aren’t mentally strong.” And instead of drawing a boundary, instead of dropping a dead end conversation and going home, I asked, “Does this experience asexualize me?” He said, “What?” And I said, “Does this desexualize me?” He said, “What?” And I said, “Can you ever view me sexually ever again?” And then it clicked. “Oh,” he said, “Yeah. You still pretty.”

I went home and asked myself: Who am I when I’m stripped of everything?

My ex texted me a photo of a bag of wild berry Skittles—one of our favorites—and a fist unclenched inside me: I was not alone. Together, we ate the Skittles and watched reruns of MTV’s Made. As a tenth grader threw out her stuffed animals in a ritual to embrace her inner pageant queen, I told my ex about my mission to unlearn the male gaze. I said something, like: I wish men cared enough about women to sit at a table and theorize about why a woman is the way she is. Like, I just feel like women spend so much time considering the male perspective; like, we walk in circles trying to understand why they do the things they do. And partly because we have to, just to survive; like, we have to put ourselves in a man’s position at all times because America was made for white men. We don’t even have a choice in the matter; the decision boards of every major media corporation are dominated by men—so what we see and consume is almost exclusively funneled through the white male experience. And then personal experience also forces us to walk around, constantly trying to not let the injustice some egomaniac in school or work or love or everyday life put us through affect our productivity and personal relationships. On so many levels it’s so difficult to know what choices are the result of your own desires, or are just some attempt to impress men—or, at the very least, minimize their negative reactions to you. Men, especially white men, have no idea what it’s like—nothing forces them to consider us with the same level of depth. It’s fucking exhausting. Like, I’m so tired of considering them. What’s it like having a portion of head space that’s all your own? Like, I don’t want to spend my time in therapy drawing a list of non-negotiables for some hypothetical man. I want to render the man completely irrelevant. (What was it that Margaret Atwood said? Oh: “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman.”) My ex paused, and, with careful consideration, he said, “I’ve never really thought about it.” Later in the week, I took a bath and read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. She talked about “masculine protests”—Alfred Adler’s theory that says any act of transcendence in a woman is a mere attempt to be more like men. She said: “When a girl climbs trees, it is, according to him, to be the equal of boys: he does not imagine that she likes to climb trees.” Coincidentally a TikTok came up on my ForYou page in which a young man asked—with total sincerity—“Do women even have hobbies?” And I stewed over the petty role women still seemed to play in the heterosexual male imagination, on the social implications this posed on the feminine imagination; how women were so often left to recover the parts of their fractured identities with little to no accountability from the source of the fracture. I recalled a line from Simone de Beauvoir: “Woman is far more deeply divided against herself than is man.”

I asked myself again: Who am I when I’m stripped of everything?

I read about a study that found women internalize an observer’s view of themselves, and—when they think of themselves from this perspective—they place a greater emphasis on how they look than how they feel. This significantly affects their ability to be present. The article said: “When women are prompted to take on a self-objectifying perspective, they experience anxiety about their appearance and physical safety, along with reduced mindfulness of internal bodily cues, and decreased ability to focus on immediate mental or physical pursuits.” As an antidote to my own self-objectification, Simone de Beauvoir suggested that I “drown in my own image”. (Studies suggest that mirror meditation—gazing at oneself with no intention other than to be present with oneself—reduces stress, increases self-compassion, and has no negative effects on narcissism.) I decided that it was worth a shot. I looked in the mirror and poked at my own face until my pupils consumed my irises, dissociated until my own name felt uncanny and my own image began to cannibalize itself like a russian doll. (The self, I was learning, was a rabbit hole you could fall down: when you begin to seriously question what fulfills you outside of other people, you subsequently begin to question whether anything truly fulfills you at all.) After that, I decided I needed to experience the horror show of my own feminine self-actualization through the scope of Satanic imagery: I re-watched The VVitch. Thomasin, the anti-heroine, teases her younger siblings by telling them she is the witch from the woods. “I’ll make any man or thing else vanish I like,” she says, right before keeping true to her promise—after the death of her siblings and her mother and the patriarch who brought them all into this mess, she makes a deal with Black Philip. When he asks her if she would like to live deliciously, she says yes. Naked, she walks out into the woods and joins the other fallen beauties in their dancing. (I have always found this scene deeply satisfying—like I’ve always been waiting to be offered the kind of freedom that can only be achieved through damnation, to finally let go of the world of men in a way that is ruthless and cutting and eons away from the pressure of others’ expectations.) At the film’s close, I remember thinking: I need a clean break, but I don’t know what to break. Later that night, a girl on TikTok said she cast a love spell on her crush when she was in the sixth grade. She stole from her parents’ pantry and from the farmer’s market—she stole unspecified objects from the crush himself. She mixed it all up in a bottle and then buried it in the direction of his house. “He still messages me,” she said. And I wondered at the power: was putting a person in that kind of purgatory adequate retribution for the sting of unrequited love? That’s one way to get a man to consider you as a person, I thought.

A few days later, my friends and I had a seance.

It was a nightmarishly white gathering of cultural appropriation—we burned sage and incense and put on music that sounded ageless and Egyptian. We asked the ouija board if there was anyone out there, and we were subsequently acquainted with a spirit named Bev. (She was a pothead in the sixties who liked to be choked during sex.) In between ghosts, one of my friends asked me, “What’s the worst part about quitting alcohol?” And I gave her the easy answer: the hardest part about quitting is quitting. I sidestepped the part where I explained that, when you cut one thing out, another thing pops up. (I was quickly realizing that sex and love could be just as intoxicating and dysregulating as alcohol, could be just as effective a distraction from the painful inner work that was healing and growing and becoming a stable person who wasn’t divided against herself.) Later that night, The Crush resurfaced in the form of a ghost emoji. (That’s the annoying thing about men, they have a sixth sense for when you’re starting to forget about them.) I responded, “The witchcraft is working,” and cast all focus on cultivating an individual identity to the wind. This was more important: I was not rejected. Why this perceived “redemption” felt so significant—whatever underlying deficiency that rendered it crucial and not as completely asinine as it should’ve been—were questions to be dealt with on a later date. This validation was a welcome distraction from my lack of inner resources: it’s insane how a single bump of dopamine can convince you that you’ve finally resolved the problem of your own existential boredom, that this one bread crumb of an external affirmation will finally make you whole; that you’ve been saved and will never have to feel the terrible iciness of your own emptiness creeping up on you ever again. (Tell me: am I being melodramatic?)

But then he vanished just as quickly as he appeared: he ditched me, more or less.

And I felt humbled by it once more, although humbled isn’t quite the right word because it cut a little deeper than that—just like rejection always did. Ugly little spiders of past hurts crawled all over me—my situationship popped back up like a poltergeist, bringing all of my unresolved shame around caring for a person who was avoidant and unresponsive along with him. It was foolish for me to believe that the old adage of getting under someone else to get over someone else could actually save me from having to process my emotions; that I could fix an already-played-out situation with yet another emotionally unavailable person and somehow make it end differently. I chastised myself: How could I allow this well of insecurity to control me? (Was I really that shallow? So self-deficient that the bare minimum was all I could ever dare to hope for? Was validation from men the only thing I knew how to live for?) Once again, I found myself by the phone, waiting for something that was obviously not going to happen—giving my time and energy to something that could take or leave me and didn’t want me on any terms other than its own—and it was a dreadful place to return to. I was about to start thinking of myself in negative absolutes, like I was always just a mistake and regret in someone else’s process. But then a grain of personal growth presented itself: some advice from He’s Just Not That Into You rose to the surface and redirected my neural pathways. Greg, that angel with the frosted tips, came to me and said: “Your only responsibility in someone else’s lapse in judgment is to yourself.” And so, with that, I reasoned kindly with myself like a parent: People only have so much time for themselves; only so much time for their friendships and other connections, their jobs and other obligations. It sucks when you don’t make the cut. I watched a woo-woo YouTube video about restoring feminine power. Some life coach barked at me about how trying to convince other people of my worth was a waste of energy. “I’d rather create a baby than have to convince anyone of anything,” she said, “that would be more effortless.” Meanwhile, in another video about detachment, a bespectacled hipster quoted Pema Chodron from beneath a vintage filter: “You are the sky and everything else is just the weather.” (I did my best to internalize these messages.) Finally accepting reality, and referring to no guy in particular, I said to a friend, “I think I was just too weird for him.” And he said, “Cat, I don’t think he knows what he wants.” (Such is life: we all eventually find ourselves tangled up in someone else’s process, and it seems as if everyone always needs something from someone who cannot give it.) With everything in mind, I finally decided to sooth my weary heart with an episode of Pen15. Maya, one of the show’s 7th grade protagonists, has grown tired of her daily problems—she’s sick of always being second best to her brother in her mother’s eyes; she wants a body free of hair and a group of cool friends who love her. As a result of her incessant longing, she starts casting love spells on a classmate named Brandt—she slips pieces of her hair into his locker; she ties his shoelaces into a “lover’s knot” and crafts a doll in his likeness that she sings to over imaginary crumpets. Quickly, however, she finds that she is not magic: Brandt rejects her ruthlessly by telling her that she’s ugly. “I don’t like you,” he says with harsh resolve. Afterward, Maya stands frozen in one spot with tears in her eyes, dressed down and dejected. Her best efforts are not only undervalued, but completely reviled. And I felt sad watching Maya return to a place of shattered illusions; I understood how quickly a heart could obscure the truth of a situation and lead a person so far away from herself that any memory of one’s better qualities felt scrubbed from history. Because, it’s true: our tireless efforts to escape ourselves—especially through the eyes of men—always wind up making us look and feel sick in the head. After that, I Googled “the problem with manifestation”—that Buddhist concept of spiritually fulfilled desires co-opted by millennial women everywhere—and I read about how there’s a fine line between the law of attraction and magical thinking. The psychologist who wrote the article didn’t write off manifestation as a cognitive distortion so much as he warned against its pitfalls. He said the fruits of manifestation are paired with hard work and personal responsibility; he said satisfaction could only be found by falling in love with the process. After months of trying to “manifest” a healed heart and stable identity, I surrendered. Okay, I said to myself, I’m ready to fall in love with the process.

And, with that, I considered writing men off entirely.

I listened to that Miley Cyrus song about buying myself flowers on repeat. One day I had the chorus stuck in my head and the guys at work were up in arms about it. “I hate that song,” they said, right before they went in on Taylor Swift. “Has she ever considered that she might be the problem?” one of them asked. (I refrained from reminding him that she literally wrote a song about that.) “You guys just hate women without men,” I said, passive and matter of fact. Later that night, a TikTok came up of a smiling girl getting slapped in the face, and guys were going wild about it in the comments. “Where can I get one of these?” one asked. Instantly, I had a flashback to something my friend said during another round of group psychoanalysis, “Men, like, kill people when they can’t have sex with women.” Looking for proof of her claim, I stumbled across the notoriously misogynistic mass shooter, Elliot Rodger. In his 137 page manifesto, he writes that women are “vicious, evil, barbaric animals” that “need to be treated as such.” He fantasizes about putting every woman into a concentration camp and “gleefully” watching from a looming observation tower as they all starve to death. Reading this, I thought: Some men do, indeed, kill people when they can’t have sex with women. I fell down a rabbit hole, watching videos of men humiliating their brides on their wedding days. In one, a groom pretended he was going to jump into a pool with his wife and then backed out at the last second, leaving her stranded with her hair a mess and her dress ruined. (Her previously elated face was reduced to what could only be described as depression.) The foreshadowing, I thought with horror. My friends told me stories about husbands who abandoned them with mortgages for houses with unfinished rooms and leaking pipes; husbands who wouldn’t let them go out but barely acknowledged them when they stayed in; husbands who had other women lined up mere days after they finally found the courage to leave them. (One of my friends described heterosexual marriage this way: “It’s like I have all the worst responsibilities that come with being single, but with none of the benefits of actually being single.”) Eventually, a TikTok came up, saying, “Marrying a man is the most dangerous thing a woman can do,” and I had to agree. (As Jessa Crispin put it in her memoir about toxic masculinity in the midwest: “Sometimes men kill their families.”) And yet, I thought, to fall outside of the family structure, outside of the sanctity of marriage—to run with the black sheep and refuse to keep the secrets of these constructs, to carry on their traumatic cycles—is to be made vulnerable. (As Jessa Crispin also put it: “Marriage is an instant structure to lock yourself into, an easy series of decisions about what to do with your life and how to make it work. At the same time, you make yourself legible; the world around you understands your place and the role you play when you announce yourself as wife, as husband, as mother, as father.”) With all of this in mind, I realized I wasn’t even able to announce myself as a “career woman”—the one type of single woman society could forgive. And I came to the conclusion that I’d not only begun to question who I was outside of love with men, but who I was outside of marriage and family and motherhood. (Was I a pretty shape? A forever teenage runaway? A crone out in the forest with a single milky eye?) At some point, I got to the end of that novel about the dystopian world where humans are bred to be consumed as meat by other humans, and I understood it as a metaphor for how a patriarchal society, on some level, still views the average single woman. In the end, the narrator develops a relationship with a female who has been bred for meat. Eventually he impregnates her and trains her to live in a house, showing her how to use cups and utensils. They watch TV together and sleep together. He names her Jasmine. And just when you start to believe that he might love her, that he might actually see her as a fellow human being: the baby is born. The narrator and his estranged wife take the baby from her to be raised as their own. And, as Jasmine reaches and reaches for the baby, she is unable to cry out because all the bred-for-meat humans have severed vocal cords. The narrator clubs her in the forehead and slaughters her in the garage. (I should’ve known, from the very beginning he’d said: “She’s gorgeous, but her beauty is useless. She won’t taste any better because she’s beautiful.”) I almost threw my kindle across the room. Audibly, I asked a fictional character, “What was the point?” I wrote my first book review ever on Amazon like a Karen scorned: This book adequately demonstrates how lust for the family unit can make a person deliriously selfish. But, alas, I knew my discontent was more personal than any criticism I could make about the capitalist ploy that is the nuclear family. I saw myself in Jasmine, obviously: as an object, used and discarded. I saw the story as my own, as so many other single women’s stories: a story of how a man loves to play the role of a valiant savior just to slit your throat—just to take your metaphorical baby and hand it off to the next woman—in the end. (As one of those cheesy viral quotes professes: “The same men who have clipped the wings of their women will say they prefer those who can fly.”) And, with that, I thought about how, when your dreams aren’t consumed with babbling babies and white picket fences—with a red blooded American of a man upholding the structure of your life—you can feel lost quite easily. Because there are no romanticized images of a feminine person alone with her books and hobbies and the dirty dishes that are all her own. And, even when there are, they always feel voyeuristic, and, somehow, punitive. (Please see the movie Young Adult.) Meanwhile any depiction of trauma inflicted upon women by men within the heterosexual couple feels hazy and distant between all the happily-ever-after rescue fantasies we were raised on. The messages all conflict to a point that’s dizzying: Men are your greatest threat and your only answer! To finally stop and question it—your compulsive heterosexuality, how the male validation you’ve been conditioned to crave has only ever made you sick with disappointment—is to stop and realize: Holy shit. I might actually know who I am if I just stopped dating men.

Of course I found myself on single-women-by-choice TikTok.

A woman in her early forties came up, talking about how she was beginning to accept that she’d probably be single forever. She said: “I’ve been in so many relationships, long relationships, and no one has ever, ever, added value to my life or made me feel like I was enough.” Women in similar positions were flooding the comments: “The fact that there are 95k likes and this video has been shared 9,000 times.” As my nail tech drilled white polish off my fingernails, she told me about the girls and women who sat in her chair and talked about boyfriends and husbands who wouldn’t allow them to paint their nails or get their hair done in a certain way; they admitted to never having experienced a bodily function in front of the men they’d been intimate with for years. “That sounds fucking miserable,” I said, right before I had her paint my nails cherry red in an act of defiance. After that, I read that viral article from Psychology Today about the rise of lonely single men. The psychologist said the rise of single lonely men was due to an increase in standards among women. “There’s less patience for poor communication skills today,” he said. Meanwhile, a guy on TikTok explained the rise of lonely single men a little more bluntly. He said that men have yet to realize that—now that they are no longer needed for bank accounts and property—they need to become more likable. He said: “[Before women were allowed to work], men could get away with being shit, and they’ve held on to that mentality even though that’s no longer true.” In other videos, millennial women detailed watching their married mothers maintain careers and still bear the brunt of responsibility when it came to housework and child rearing. As they saw their mothers struggle to do—and be—everything, with little to no help from their fathers, many of them vowed to themselves: That will never be me. And I felt that—absolutely. Staying true to my cannibal book theme, I read a novel about a female serial killer who murdered and ate all the men she loved. At some point, despite her “passionate” romances with men, the female serial killer claimed that a friendship with another woman was the greatest love she’d ever known. She said: “Our female friends, the close ones, are the mini-breaks we take from the totalitarian work it requires to keep up the performance of being female.” Glossing over entire paragraphs detailing the meal preparation for her favorite beau’s liver, I kept what she said in mind.

I started making a conscious effort to find solace in other women.

I read about historical communes developed specifically for single and, primarily, childless women during a time when women were usually limited to two options: devote yourself to the church or bear children until your pregnancies kill you. They were called beguinages, and they produced women philosophers, theologians, writers… (Unburdened by children and family life, women in these communities were free to be thinkers without the constraints of men and the fear of premature death.) I read about modern day “mommunes” where divorced mothers split mortgages and live together in platonic bliss between bright pastel walls and scribbled drawings. All of them said they felt more fulfilled in their sisterhood with each other than they ever did in their more traditional households. Upon learning all of this, I confessed to my friends, “Men often make me feel disgusting and unwanted—other women are the ones who have always made me feel beautiful and desired.” And they all agreed with a level of catharsis, having been shut off and unconscious of the way most men actually made them feel for so long. After that, I decided to admire more women, to pay closer attention. I noted the way one of my friends lived alone in a house filled with overgrown plants, among cats and a little frog and a small congregation of guinea pigs. It was like some kind of menagerie, and yet, somehow, everything was spotless. I stood in awe of her ability to take care of things. She had me thinking that Chuck Palahniuk was right: I am the combined effort of everyone I’ve ever known. Eventually, at a bar, I admired a girl in her early twenties with creeper shoes and fishnet stockings underneath ripped jeans.

We clicked instantly.

She told me about the deterioration of her long term relationship, and the resounding confusion—how insufferable dating could be. I told her about the situationship that put me into a six month long existential coma by quoting A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” And then she scored me an ex con with a nice jaw line’s phone number because I never learn my lesson. Afterward, he texted me, “I saw the way you looked at me, and I knew I was going to try to snatch your soul.” (I understood: this was not a swooning obsession, nor a budding romance spreading its roots into the long term. This connection was hard and fast and purely carnal.) We engaged in aggressive sexting for approximately two weeks, and I lapped it up like milk to kitten because: we love a soul-snatching sociopath. Quickly, however, it plummeted from euphoria into sickness: he started feeling stung by how I preferred the comfort of my essential oils and weighted blanket to his king bed. And, therefore, things promptly ended when he touched down on something solid inside of me. He said, “You think you’re submissive, but you’re not.” He started to say something crass, like: A real sub would suck a dick until she threw up if she had to. (He was more honest than most men about what he was looking for, I guess.) He said, “You have a will,” as if it were an iron rod running through me. He said, “You have a sense of control and you don’t give yourself up easily.” He said, “It’s okay. I’m just not what you’re into.” And I had a flashback to a time when I asked my situationship, “Do you want me to be happy?” I remembered how it had made him uncomfortable, and cagey. “Yeah, why?” he asked. And I said, “Because some men don’t want the women they’re with to be happy. They just want someone to control.” After that, I went home thinking about how The Ex Con’s rejection of me had felt more like a list of compliments than criticisms. I looked in the mirror and found that I was wholly there, finally letting the chips fall where they may, untethered by the consequences. I didn’t crash. I thought of nothing: not of my loss or his loss or of matters of too good and not enough. It was what it was, and I didn’t mind what it had been. And, therefore: I was ready to accept what came next.

I caught my situationship in one last lie.

I came face to face with a woman who had also dated him. “He tried telling me you were crazy when he first started seeing you,” she said. And I looked back at her, dead-eyed: I could feel it. I thought about how he’d painted a mental picture of this woman as an ogre; how he’d made her sound desperate and ugly. I realized that all I saw was a beautiful, rational person standing in front of me—normal as anyone. (I may have not found a cozy nook of sisterhood inside her, but I did feel as if I’d peered into a mirror.) And so I feigned anger to mask my thudding disappointment. (What was the point of always sitting back, poised and stoic and taking all sides into consideration, when all they ever seemed to do was disregard your moments of grace, turn around and call you crazy anyway?) I considered how I’d always felt as if he’d been waiting for me to throw a punch, to reach the point where I was so angry that I hated him, just so he could throw it back in my face and use it as a point of reference for the “insanity” that is women. But I knew, for me, that day would never come. Because I’d never been very good at being the kind of person who viewed love as a game to be lost or won. I was just so fucking tired. I had nothing left to give. So, I went home and I removed my makeup and I took care of my skin. I looked in the mirror and reaffirmed something redeemable. I paid homage to the places he took me, lamented his virtues and relearned our connection as something that had always been black and blue. I got under the bed covers and listened to a guided meditation for heartbreak; I listened as a guiding voice told me to imagine my relationship as a flower. A white daisy came to me, summer-y and fragile, so pure and so sweet. The guide asked me to imagine the flower withering until it disintegrated into nothing. She told me the soil would dry; that it would be nourished by rain, and, in its place, a new flower would grow. She told me to picture my new flower, and I saw a purple and yellow pansy, light and deep and velvety. Mature and wise—so open-faced and proud. (I remember hearing somewhere that karma exists on a cellular level; that it’s not an external force imposing itself upon us, but something that already lives on inside us…) As the world came back into focus, I wondered: Maybe it’s true. Maybe the older you get, the less capacity you have for rage.

And so, I properly grieved.

I gorged myself on Oreos and milk and a rapid succession of Diet Coke. I ate a single green bean. I read a line in an article called How To Get Over a Guy In Ten Days. It said: “Needing closure is fake. You’re never going to hear what you think you want to hear.” Later, a TikTok came up, explaining how the language around our romantic entanglements has changed overtime to benefit capitalism; that terms like “hook-up” and “situationship” have developed to invalidate our temporary romantic connections, ultimately reserving “adult” words for the kinds of committed, long term relationships that result in a nuclear family of consumers. The woman ended the video with some words of encouragement. “That’s your lover,” she said, “don’t diminish it.” And so I finally forgave myself for having feelings for a person who was unresponsive and avoidant; I reminded myself that just because other people view a small flame as something inconsequential doesn’t mean that another person’s need for time and space to process its meaning is abnormal. (Denying my own feelings, punishing myself for having them, criticizing my vulnerability and inclination to freely open myself up to others was an assault to my femininity.) After that, I saw a photograph of a school of happy-faced blowfish and reminded myself that so much was still possible. I looked across the room and saw a man who was beautiful—like actually, truly, beautiful—and I thought to myself: Oh yeah, there’s other people. He turned out to be a veteran visiting from overseas, and we started texting back and forth across a vast space about our days. He told me he wished he could bring me a cherry blossom milkshake, and I told him I wished I could bring him a clear April night, cool with rain. It was nice, finally liking someone who actually liked me back. And, when he returned to the states, he taught me how to skateboard on a path out in the blossoming woods with the sun poking through, tree by tree.

For a moment, it seemed as if I’d been handed back everything I’d lost on a silver platter.

But then that quickly divulged into the age-old warning: be careful what you wish for. There were red flags here and there. Like, I asked him what the stupidest thing he’d ever done was, and he told me “eating too much ice cream”. (I had to resist the urge to say, Sir, you once had a dick piercing.) There came a point where he told me that not very many break ups had made him unhappy. He said, “Usually when I lose something I really like, I can easily replace it with something else.” His stories of his past relationships seemed vague despite the length in which he told them; the language he used was cloudy, a string of adjectives lacking in concrete memories and experiences. All of his exes had been “troubled”, a conglomeration of neuroses that reminded him of his mother. He told me a story about an ex, standing inconsolable in the shower, screaming, “You don’t love me anymore, you don’t love me—” But the story leading up to that point was hazy. He couldn’t tell me anything about what had brought them there, and I had premonitions of me in the shower, inconsolable… It felt like I was constantly trying to pull unadulterated truths about himself from him like magic tricks, like I had to manipulate my way into his heart. Eventually, I told him, “I feel like I’m always trying to pry things from you, like I’m sharing so much of myself and I’m not getting anything back. It isn’t fair.” And he said, “You’re not the first person to tell me that.” Finally, there came a point where I caught a glimmer of something that I’d already had: I was angry with him in a side alley. I’d walked in on him smiling down on another girl in a bar, and something about it had seemed so smug. He looked unrecognizable compared to everything he’d shown me. “Something’s up,” my friends had told me.

His smile always seemed so out of context after that, and it caused a fissure inside me.

He texted me about how he’d lit up upon seeing me murderous with jealousy. He said, “I was happy because it made me feel like you’re attached to me.” And I had a flashback to a quote from that book about the female serial killer who ate all the men she loved: “Some men need to witness female rage to believe in that woman’s love. Some women need to get angry to experience that love. Some people grow together like horrible species of lichen.” Needless to say, some part of me kept wondering: Is this connection healthy? I feared manipulation, and I questioned how often the situation was actually making me feel good. And yet—I was waiting for a sign, cut and dried, to give weight to my paranoia. (Of what, I couldn’t decide.) Trying to quell my overthinking, I impulsively booked a jacuzzi suite for The Veteran and I. But then, just as quickly, I told him not to come. I laid alone in the king bed and cried as I felt a pang in my heart over all the Japanese snack cakes and Diet Cokes in his fridge. The balanced meals he’d cooked for me, and all the times he’d held space for my anxiety, saying, “Everything you’re going through sounds very human to me.” I stared at the ceiling and listened to the tub drain as I let go of yet another dream—I just couldn’t shake it, the feeling that he was hiding something. After that, a song came up on shuffle: You can’t always get what you want, but sometimes— I invited my ex to the room instead of eating some pizza and wings that I had no appetite for anyway. And, as I waited, I wrote about how my ex reminded me of my grandfather every time he left the room, quiet and gentle as a petunia speaking for itself—one of the striped ones; how he was a graceful balance of feminine and masculine traits. I wrote: Is this it? The end of the turmoil? The breaking of a toxic cycle? (When I first saw him, I knew: he was a person you could tie your ship to. So sturdy and wholesome and good. Every time the dust settles from my latest mental health crisis, he’s still standing. The strongest man I’ve ever met. Proof that a time comes when enough is enough and you’re ready to marry the face of your healing…) We sat across from each other in that massive bathtub and cried together. He said, “I can’t keep being here every time you hit rock bottom.”

I believed every good thing in the world about him, and, still, I had to be certain.

I continued to see The Veteran despite the red flags and my reservations, as if it were some sort of puzzle that I had to solve. I paid a tarot girl $30 on TikTok to give me a “love” reading. She told me that I was coming out as the high priestess upside down. She said, “It could be that you’ve been feeling like there’s some sort of harm hidden or secret agenda, or there’s some sort of disconnect from your intuition when it comes to why you haven’t found somebody.” She told me painful situations from my past kept me stuck in a loop, thinking I needed to “figure people out”. And I realized she was right: I was stuck in a loop, trying to figure someone out. In an attempt to come unstuck, I started moving my things out of my ex’s apartment. Walking up and down the stairs with my books and trinkets, I kept counting on a sign tacked to a neighbor’s door to get me through: Walk by faith, not by sight. I began to notice that The Veteran always seemed to be moving, constantly leaving me to look around rooms, waiting and wondering what he was getting up to on the other side of the wall. I began to second guess myself. I speculated about self-sabotage: maybe I was just looking for reasons to wreck a good thing. But then a pamphlet at the Wal-Mart pharmacy appeared to me like a warning: There is no life without risks. And I wondered whether the “riskier” options—the ones who cause the most pause—are in fact, the safe options, especially when it comes to love. I wondered whether dysfunction—constantly fretting and looking around rooms—could feel familiar and cozy in its ability to light our brains up like wildfire. (What if safety and stability was its own kind of risk? Perhaps the tranquility of actual love was scary to the kind of person who didn’t know what to do in the quiet spaces of tedium that allowed for personal growth, reflection…) I wondered whether freedom from chaos was terrifying to the kind of person who didn’t know what to do with it; who’d only ever known high highs, and low lows, and the fight for survival. Signs screaming GO BACK TO YOUR EX seemed to be everywhere. (The world was in the heat of Scandoval and I could imagine my ex repeating Ariana’s words to Sandoval over and over again: “I would have followed you anywhere.” I watched an episode of Closer To Truth, and some professor said: “Soulmates: you can’t get rid of them.” I read a book about a deep friendship between two video game programmers, a guy and a girl. Explaining the nature of his relationship with the girl to a friend, the guy said: “It’s better than romance. It’s friendship.”)

I sat and quietly waited for the other shoe to drop with The Veteran until it finally did.

I told him I was moving to Seattle to be with my nieces. It was a snap decision set in stone between my sister and I overnight. He retreated from me, told me that he had lost his taste for Diet Coke and some variation of how my decision had dashed his hopes to pieces. “You know, I’m human,” he said. And I held space for the fact that he was flawed and imperfect with his own set of reservations and traumas; that there were things inside which caused him to recoil and withhold pieces of himself—that these things didn’t necessarily beget malevolence, but, more often than not, implied a deep hurt and fear of rejection. (I did that, I swear.) But then, the next morning, he went about his day around me—vacuuming, eating, going to the bathroom—without really saying anything. And I kept waiting for him to stop and talk to me. I wanted to help him process the moment, or, at the very least, hear him say that he just wanted to be alone. But there never came any moment of vulnerability. Instead, he abruptly announced, “Well, I’m going to the gym,” and something tightened in my stomach. Seeing the look on my face, with what I could have sworn was a smirk, he asked a rhetorical question, “You’re really uncomfortable, aren’t you?” After that, I went home and thought about how I didn’t want to spend my life, anxiously—patiently—waiting for a person’s behavior to make sense to me; trying to cram myself into someone else’s life as I lost my sanity and they got to keep their routines without compromise or consideration. I was bored with sitting around watching men do things unencumbered by how those things affected others. And, that night, when The Veteran sent me a series of concerning texts, punctuated by the declaration, “I am so angry”; when he admitted to me that he’d downed an entire bottle of Jager after always having presented himself as someone who wasn’t much of a drinker, I remembered a line from a bell hooks book about the search for female love: “Working to be close to someone who is not interested in sustained closeness not only depresses the spirit, it makes you a perfect target for aggression.” I considered how often I’d suffered for love, how I used to hold my heartache up like a badge of honor. I pictured the empty bottle of Jager and decided I couldn’t romanticize that kind of senseless longing any longer; that I couldn’t dwell in the realms of unrequited love, waiting for some dude who was incapable of meeting my needs to throw me a bone. I thought about this TikTok where a girl talks about how a heterosexual woman will consider how a relationship problem is her fault, in every possible way, before she’ll blame her male counterpart. She said: “What I think a lot of [men] don’t understand about women is that we have been raised to analyze you, to think circles around the reasons you do the things you do… and what ends up happening a lot of the time is any sort of focus on ourselves is lost.” Once more: I pictured the empty bottle of Jager. And I realized that I had no interest in trying to figure the Veteran out. I had no interest in analyzing his inability to reveal himself. It wasn’t up to me to piece together the traumas of his childhood, to create a roadmap of his unfulfilled longings and try to make up for them. I had already watched too many women bear the crosses of their boyfriends and husbands, and I just couldn’t see myself playing that role, dumbing myself down into a guidance counselor for someone who was too proud to get a real one. I had enough of my own problems. I’d faced enough of my own challenges. I was tired of romantic love always feeling like an endurance test. I’d already gone to therapy, taken responsibility, allowed others to be themselves…

(The empty bottle of Jager was an invitation to an unhappy pattern that I’d been trying so hard to unlearn.)

I thought about how Clarissa Pinkola Estes wrote that, as feminine beings, we start off “naive”; that we are conditioned to “be nice” by overriding our intuitions. She says we are “taught to not see, and instead to ‘make pretty’ all manner of grotesqueries whether they are lovely or not.” She says, as naive women, we fall victim to predators, and—although we come out stronger and wiser for it every time—the process repeats until the lesson finally sinks in. She says what often keeps a person locked into this pattern is a determination to “cure [the other person] with love.” She says: “Somewhere in our minds we know this pattern is fruitless, that we should stop and follow a different value… But there is something compelling, a sort of mesmerization, about continuing the destructive pattern. In most cases, we feel if we just hold on to the old pattern a little longer, why surely the paradisiacal feeling we seek will appear in the next heartbeat.” Like any other destructive cycle, I realized that being with the Veteran provided a euphoric level of alleviation from my psychic unrest, my deep boredom—that gaping emptiness—but, ultimately, when the high subsided, it exacerbated my pain; and maybe finding evidence to validate this internal struggle was less important than simply acknowledging the fact that something about the situation was making me feel like shit. Again, I drew upon the power of He’s Just Not That Into You, and considered a passage: “Forget about him and his good qualities. Even forget about his bad ones. Forget about all of his excuses and what he promises. Ask yourself one question only: Is he making you happy?” With that question in mind, I began to contemplate the difference between attachment and love, and I came to the conclusion that how you feel when someone’s attention is withdrawn is just as important as how you feel when you’re basking in its glory. (If you feel scared and uncertain, if the creepy crawlies lay siege every time your partner leaves the room, then maybe it’s just an attachment, maybe you’re just in love with the feeling you get every time they look at you.) After that, I decided to watch the film adaptation of He’s Just Not That Into You, and I listened as the male antagonist shat all over “the spark”—that little bump of dopamine I got every time my situationship winked at me. He said: “Guys invented the spark so they could not call and treat you kind of badly and keep you guessing, and then convince you that that anxiety and that fear that just develops naturally was actually a spark. And you guys all buy it. You eat it up and you love it. You love it because you feed off that drama.”

(Dear reader, I was triggered.)

I looked my endless boredom in the face and thought of an infographic about BPD and obsessive attachments: “If a feeling is not completely overwhelming me and taking me over, then it’s as if I’m not feeling it at all.” I wondered: When am I going to finally give it up? (It was becoming clear to me: there was no escape. This emptiness was mine to keep, an open room that I needed to step inside. To face its blank walls with the clock ticking in the background, to try and make pictures on it with dust from the floor, to derive some kind of meaning from the sun beams that hit it at dawn, to create lonely shadow puppets in the moonlight upon nightfall: were these small acts of subversion what it meant to be sober and human? Was the beauty of our days not to be found in sparks or big booms or even slight shocks of static, but in the little luxuries, like a Blueberry 7/11 coffee?) I went doom scrolling to distract myself from any more revelations, but to no avail. A TikTok of a girl came up, talking about how whenever she asks someone why they love a specific person their answer often pertains to how that person makes them feel. She said: “It’s just not a strong foundation for actually building an empathic honest relationship.” She said it was self-serving. She said it was demanding. She said it was all about finding a blank slate of a person to project our fantasies of a perfect partner who is going to come and save us from the mundane, boring lives we’re leading onto. I was about to scroll up and cut her off, but then, sighing, she admitted that letting go of the fantasy was hard. She said: “It’s grief. Especially if you’re a woman.” And, silently, I agreed, having always believed that he was out there, just beyond the horizon. I thought about how, as a pre-teen, I’d gazed out the car window on long road trips with my parents, passing through small towns, and often wondered: Perhaps, if I’d been born someplace else… It was a homesickness for another life—a life where I was made right—manifested as some dream of a man. And I wondered whether I could blame my Christian upbringing, whether romance was just another way of longing for God in a simulated world peppered with strip malls and fast food signs…

I quieted my heart.

I turned on Kacey Musgraves and listened as she sang about being alright with a slow burn. I told my ex, “You have my undivided attention.” I decided that true love could be revealed if one only answered a simple question: Who do you want to see when you’re sick of everyone’s shit? After that, my ex said, “I just want to go back to having fun.” And I said, “Okay,” as I let go of “the spark”—a life of staring out windows and longing for cosmos—and got down in the mud with my favorite playmate. I let go of my fear of boredom and stagnation, silenced my thoughts about a question posed by Jessa Crispin: “What’s worse, to be inside the couple with all of its obvious compromises and threats, all of its pains and boredoms, or to be outside of it?” (Why don’t people talk more about how scary love of the life-long variety is? About the effort and the doubt and the blind faith one puts into it? The waxing and waning of hope; the way it dies, and then, miraculously, springs back to life again? The day by day choice you’re making, and the strength of will required to keep making that choice? The way you’ll wake up one day to discover the big picture—finally realizing that this love is both the easiest and hardest thing you’ve ever accomplished—and, completely terrified, how you’ll ask yourself rhetorically: Am I… happy?) “Do you think you’re afraid of getting hurt?” my ex asked. And I thought of an Alan Watts quote: “You have a great endowment of brain, muscle, sensitivity, intelligence—trust it to react to circumstances as they arise.” Once again, I let go. I got the tips of my nails painted black and told my friend, “I’m in a transition phase.” He looked me in the eye and said, “That’s a harsh transition.” I spent my nights looking at the moon. I wrote my stories, and made my friends presents. I went for long runs and marveled at my body’s resilience. I did everything I could to fill that vast space with things that were self-serving, but productive. And, when the day finally came where I woke up and realized I wasn’t drinking six cups of coffee just to feel alive, my mother looked at me and said, “Your eyes look brighter.”

I kept my doors open where I wanted them left open.

My situationship re-entered my life. He got me a McDouble at 2 in the morning, and I told him about how my job tried to make me take out my nose ring—something that ultimately led to my decision to move to Seattle. He said, “Just think, when that piercer threaded your jewelry through, your whole life was coming together.” After that, he took the long way back, just like he always did, and I wanted so badly for the road to keep going. (This has always been the case with me, always wanting more more more than what a person can possibly give me.) The next day I woke up with what felt like a hangover: a migraine pulsed above my right eye, heavy again with the hopelessly pervasive hope that an already-played-out situation could somehow end differently. I sat on my parents’ stoop in the humid July air, looking beyond the haze of smoke rolling in from the Canadian wildfires. The evening was golden and thick with crickets, and I realized I was crying from the relief of forgiveness. (Have you ever had so much faith in someone else’s goodness that you could feel the anticipation of their untapped potential coursing through you like poison? Have you ever realized that there comes a point where you get to drop all judgment—your preconceptions—and finally love a person in equal parts for who they are and who they are not; not for who they’ve been or what they could do or how they’ve made you feel, but for who they are in a single moment, freed from all expectation?) I considered this quote from that book titled Acts of Desperation: “What power men have had over me seems more like a natural fact than a reason for me to hate them.” I forgave the world for being bland, for stringing me along with the false promise that some grander life filled with sparklers was always waiting around the corner. I forgave men, thought about this line from an essay about the artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s nude paintings of women: “To insist that men are wrong to see women in any way other than how they wish to see themselves—that is, how women inwardly see themselves—prevents us from reaching a fuller understanding of ourselves that can only occur when we begin to see ourselves socially and relationally.” (How could I not love men? I have learned so much about myself and the world through my relationships with them.) A ladybug landed on my foot, and I saw the world through a pair of rose tinted glasses—I swore I caught a glimmer of a spark flaring high above some maple trees. And I realized that my relationships had always been my passion, that compassion had always run red and hot through me: I could admire my space in a man’s repertoire and lose nothing. I considered one more line from that essay about Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s paintings: “The way men see reveals not men’s power but their yearning; their desperate need for tenderness in a world that can be hard and unkind and which turns men into cogs within the economic machinery.” I looked at my ex and thought: This man is my family.

I laid the bottle down at his feet and pictured my niece in a flower crown.

I asked myself: Who am I when I’m stripped of everything?